Remembering My Friend Hobie Kistler

LT Hobart Kistler, USN, SC, (USNA '13) passed away Friday, April 30 in a tragic car accident. We shared three years together on USS Louisville, where he had a profound impact on my life.

I’m sitting at my desk in the family cabin in Lake Tahoe. It’s a small and simple room with white walls, wooden accents, and a bookcase. I’m looking out the window at the evergreen pine trees with the phone up to my ear. I’m calling Hobie because I’ve just botched telling one of our favorite stories from our submarine days.

I remember the basics of the event—Jon got tased by a stranger at a karaoke club in Japan, the safest country in the world. But I don’t remember the details. Did this happen before or after one of our sailors got arrested and thrown in Japanese jail for possession of illegal drugs? What was the progression of liberty lockdowns again? We had been restricted to base, forced to travel in groups of six, could only go out in uniform, and required curfew at 2100 (that's 9 PM). I just couldn’t remember the sequence of events to tell a logical story. Hobie cleared it all up for me after referencing his notes titled Naval Adventures Vol. 13.

A year later and I’m at a recruiting station in San Francisco. The recruiting station is steps away from the famous Ferry Building on Embarcadero Road, where small waves lap against pier pylons that used to serve as tie-ups for Navy ships and submarines. I can smell salt in the air. I’m sitting across from a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed new recruit to the submarine force, answering questions about life underwater. In particular, he wants to know what the food is like. Since he’s already signed the paperwork, I have the luxury of being dreadfully honest with him.

However, I’ve blocked the memory of just about everything I ate during those three years on the USS Louisville. I find myself in need of Hobie again. I step outside into the salty air and dial his number. He’s happy to take ten minutes from his day to re-educate me on the culinary victories and defeats of Food Service Division. Creamed chip beef. Hot dog meatloaf. Beef cubes. Hamsters (aka Chicken Codon Bleu. The Canadian Navy, who I served with for two years, calls them Chicken Twinkies). Pizza with tuna and jalapeños. An Alaskan crab dinner which we blew the entire quarterly food budget on. And of course the infamous shred biscuits, where the cooks claim to have mistaken shredded Confidential papers for flour, but we all knew it was a sick practical joke.

It's another time and I’m on a date at a swanky bar. It reminds me of L'Aperitif at the Halekulani hotel, which was Hobie’s favorite. He would always convince our friend group to start a night out there. It’s a bar where tables are blanketed with fresh white linen, the room is lit only by candles, and a menu with ingredients you have to use Google for. Henry, the bartender dressed in a suit that puts our dress blue uniform to shame, has worked at L'Aperitif for more than 20 years and knows Hobie by name.

Back on my date, I’ve had one Old Fashioned already and I’m trying to open up and be vulnerable to stimulate interesting conversation. After our deployment to Asia in 2014, I was in a bit of a dark place. The many days at sea, high-stakes missions, and relentless tempo of operations really took a toll on me. On top of that, my girlfriend at the time broke up with me two days after we touched the pier. It all culminated in a bout of drinking at the submarine birthday ball which was held the same week we returned from deployment. I got so drunk so fast that I have to rely on others to remember the evening for me. Thankfully, a few text messages to Hobie sent from the bathroom of that swanky bar got me the details I needed.

He reminded me about my obnoxious heckling of the speaker who was droning on for forty-five minutes about how wonderful submarines are. Everyone wanted the talk to end so we could eat, but I was the only one whose inhibitions were lost enough to say something. I had no recollection of the full bird captain who chastised me for being disrespectful. I continued on my heckling journey behind the protection of my neon-colored, outrageously large sunglasses, which I called “the hater blockers.” I was so bad that my friends were getting in trouble too, simply because of me. John Grider got royally chewed out by the executive officer for my poor behavior. I chanted Hobie’s name at the top of my lungs as he participated in the cake-cutting tradition being the ball’s youngest ensign. Without Hobie, I wouldn’t have any knowledge of an important time in my life when I drowned my personal difficulties in alcohol and disrespect.

It’s May 1st, 2021, and I’m sitting at the same desk in Lake Tahoe that I called Hobie from to get the details on the tasing story. I’m staring at the same pine trees swaying in the wind and watching steam rise up from the last remnants of snow being baked by a warm morning sun. Tony is calling with the bad news of Hobie’s car accident. I’m in disbelief and not really sure what to do. I call the other wardroom members from USS Louisville to help spread word. I manage to reach a few of them. It only takes a few minutes because I’ve lost a lot of contacts.

I start going through old pictures to help recall the many memories I have of Hobie.

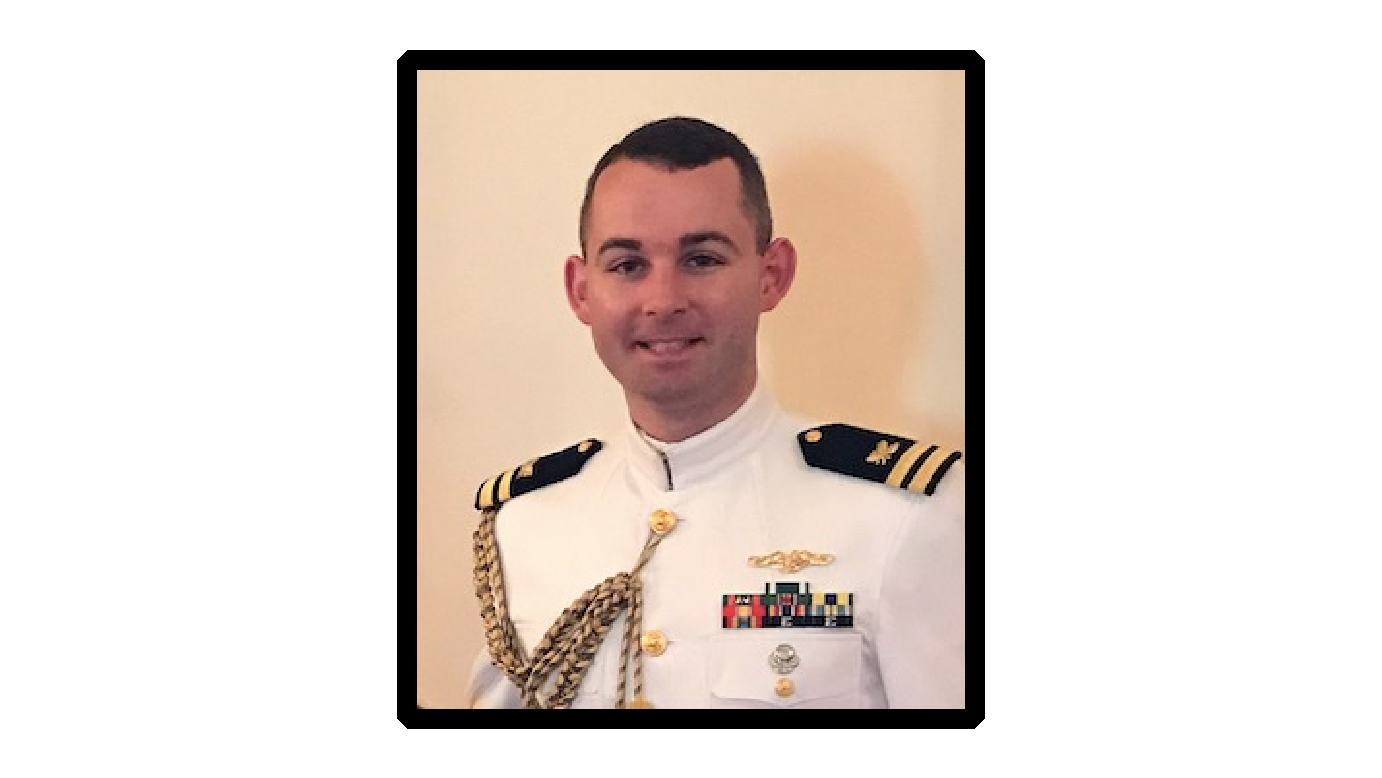

He’s tough to miss scrolling through thousands of pictures. He’s either the one with the sharpest dress uniform, or if he’s wearing civvies, he still looks the best. He wears a plaid Brooks Brothers button-down tucked into khaki shorts, secured high and tight with a belt that has nautical flags on it. It all stands fantastically upright in a pair of Sperry topsiders, posture just shy of being at full attention. It all makes my dad look modern. He’s usually cracking a giant grin or a goofy face, such that the three wrinkles on his forehead scrunch together and accentuate the mark on its right side. I’m not sure if it’s a scar or what, but it’s distinctly Hobie.There are photos from our tour of Okinawa. Hobie is grinning from behind racks of drying seaweed. He's looking at tunnel walls riddled with grenade shrapnel where Admiral Ota and 4000 Japanese sailors committed suicide rather than be captured by American forces. He loved history and always knew the significant places to tour. There’s a photo of us at the only restaurant accessible during our Japanese liberty restriction, it’s the Chili’s on base where our crew got in even more trouble due to the profane mouths of six drunk chiefs. In another picture, we are playing golf at the Marine Corps base in Kaneohe. There is one where he’s covered with green slime from half-way night (a traditional submarine party held when a months-long deployment is half-way over), which he was largely responsible for planning and executing. There’s a short video of the crew singing carols in Crew’s Mess on Christmas Day, 950 feet underwater while we are deployed on mission. It’s a morale booster that was entirely his idea, and he had to fight to get approval for. In another, we are in kayaks, paddling out to the Mokes, a pair of islands off the windward coast of Oahu where we intend to do some snorkeling and cliff jumping. One photo shows me jumping from a pile of rocks into a swirling ocean. For about four years after that picture was taken, Hobie thought it was him, and he used it to successfully match with Meagan on his dating profile. As far as I’m concerned, the picture is of him.

There’s another photo of the officers of watch team one from deployment. This has been my favorite photo for some time now. It shows all five of us, proudly wearing our underway beards (another submarine tradition) and other experimental hair styles. Unfortunately, Hobie hadn’t yet decided to grow his famous mutton chops. In the last year though, the photo has become something of a tragedy for me to look at, as only three of the five men are still alive.

I’m scrolling through our texts, where on March 6th, 2020 I thank him for organizing a video chat for the Louisville Wardroom reunion. I felt the need to apologize as I was ten minutes late and suffered technical difficulties logging on. He calmly helped me troubleshoot the issue all while continuing to facilitate the conversation on the other end. His response was, “That’s my job as Chop. Thanks for joining. Miss you buddy. First time I’ve drunk a six pack in over a year.” His LinkedIn page is open on my laptop, and prominently features his name and byline “Hobart K. Kistler, Naval Officer & Oral Historian.”

With Hobie gone, our inventory of history and story suffers a deep loss. The bright details that brought us joy, identity, and purpose are diminished and risk being forgotten without him. We lose a master of logistics and community, an arbiter of story, and a friend who cared deeply. Rest easy, Chop, I won’t forget our stories ever again.

More on Hobie: